Our History

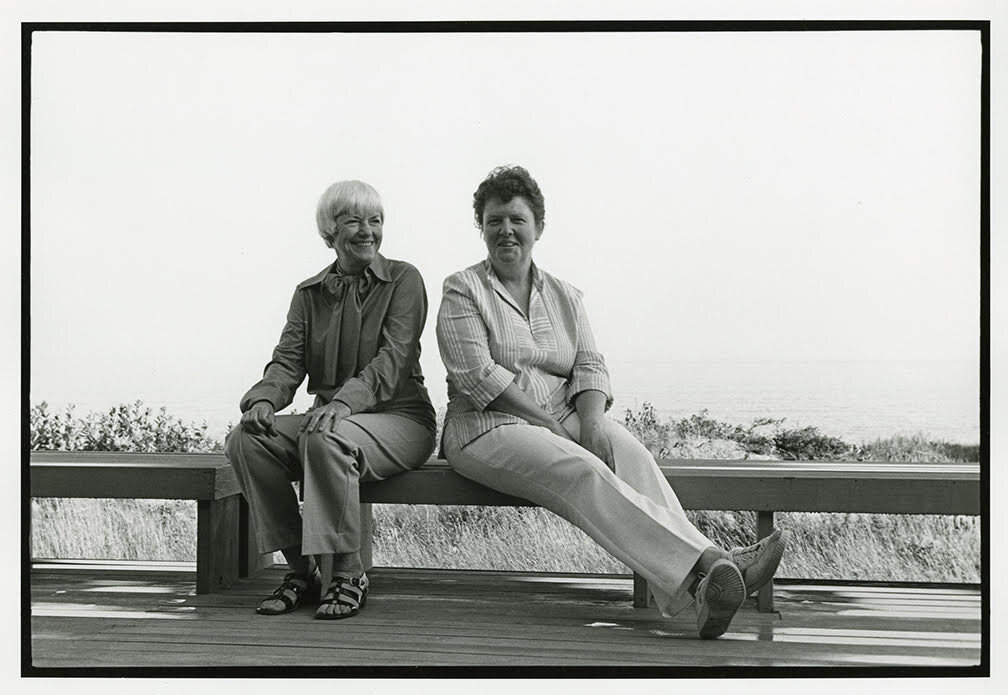

In the late 1980s, arts patron Mary-Leigh Call Smart and artist Beverly Hallam envisioned a residency for artists and arts professionals in their home upon their passing. Mary-Leigh Smart (1917-2017) was a passionate supporter and collector of Maine-based institutions and artists. Co-founder of the Barn Gallery with her late husband J. Scott Smart, she was also affiliated with the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Farnsworth Museum, Ogunquit Museum of American Art, Portland Museum of Art, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, University of New England, University of New Hampshire and Wellesley College.

Her friend Beverly Hallam (1923-2013) taught at Mass College of Art and moved to Maine in 1963 to work full time as an artist. An early experimenter with acrylics, she produced a wide range of works in many media including painting, photography, and graphic arts. Her key papers and notebooks are housed within the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art. A film was made about her work as part of the Maine Masters film series and Beverly Hallam: An Odyssey in Art by Carl Little illustrates her life and work.

With architects Carter + Woodruff, Mary-Leigh and Beverly designed their dream home known as “Surf Point,” and lived there from 1971 until their deaths. The building is set within nearly 50 acres of coast and woods protected by a conservation easement stewarded by the York Land Trust.

Inspired by artist communities in Ogunquit, ME and MacDowell, NH, arts patron Smart and artist Hallam provided in their wills that Surf Point be a retreat for artists. In 1973, they invited writer May Sarton to live and work in another dwelling on the property. In the 24 years Sarton remained there until she died in 1997, Sarton wrote some of her most important books and cultivated a stunning garden.

Mary-Leigh Smart and Beverly Hallam Surf Point

Mary-Leigh Call Smart

February 27, 1917-January 11, 2017

Mary-Leigh was born in Springfield, Illinois in 1917 and died in 2017 in York, Maine. The only child of S. Leigh and Mary Bradish Call (1877-1966), she graduated from Miss Logan’s School and then Monticello Seminary and Junior College (Godfrey, Illinois), now Lewis and Clark Community College. Her father was the editor and publisher of The Illinois State Journal and a farm owner, and her mother was a painter. She attended Oxford University in England the spring term in 1935 and received an Extra-Mural Delegacy Certificate. Smart graduated from Wellesley College in 1937, having majored in French, and in 1939, received an M.A. in French from Columbia University, having written her thesis under Justin O’Brien on Andre Gide. The same year, she was Queen of the Springfield Art Association’s annual Beaux Arts Ball.

In 1940-41 Smart worked in Public Relations for the International Institute in Boston, and briefly for the Bettman Archive in New York City. She returned to Columbia University and also attended New York University to study Agriculture and Business and Finance. In 1942, when the United States entered World War II, Smart enlisted in the WAVES as an Apprentice Seaman in the first class of officers training and was stationed at the Division of Naval Communications in Washington D.C. In 1945 she left the Navy as a Lieutenant (j.g.) and took up the management of Illinois grain farms, which she owned. She was an early contour farmer and had the second terraces in Logan County, Illinois, for which she ran the levels with the surveyor.

In 1946, she married Capt. David Guy Asherman (1917-1984), Medical Administrative Corps, AUS, after which they moved to Washington, D.C. Asherman’s family was from Ogunquit, ME and New York, and he was trained as an actor and artist. At the time, Smart belonged to the New York Wellesley Club and the League of Women Voters.

After her divorce, in 1951 she married J. Scott Smart (1902-1960), star of radio, film and early television; painter and sculptor. They built a house in Ogunquit, Maine, Three Faces East, and were active in the art community. With friends, in 1958 they founded the Barn Gallery, of which Smart was later president for six years in the 70s and 80s and vice president from 1994, until its merger with the Ogunquit Arts Collaborative. The Smarts established Lowtrek Kennel and bred Basset Hounds. Jack Smart died in 1960 of pancreatic cancer. Like her parents, Smart was an art collector, acquiring a large number of paintings, works on paper and sculpture, many of which she gave as gifts to museums.

In 1970, Smart bought 46 acres on the ocean in York, Maine, and with artist Beverly Hallam built a duplex house. In the 1980s, they established a trust to leave the property, art and assets to “Surf Point Foundation,” a non-profit foundation, modeled on the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, N.H. Smart was president of the Board of Advisors to the Art Gallery at the University of New Hampshire from 1981-89. She was one of the twelve incorporators of the Ogunquit Museum of American Art for several years. She was appointed to the National Committee of Friends of Art of Wellesley College from 1983 until her death, a member of the Collections Committee of Westbrook College (now the Westbrook Campus of the University of New England) from 1987-91, and a recipient of the college’s Deborah Morton Society Award in 1993. She was elected a member of the Maine Women’s Forum (of the International Women’s Forum) from 1993 until her death; in 1986 became a member of the Council of Advisors of the Farnsworth Museum in Rockland, Maine.

Smart served as vice president of the Old York Historical and Improvement Society at the time of the merger of York’s three historical organizations in 1982. She served two terms as a director of the Greater Piscataqua Community Foundation from 1991 to 1997 and was appointed to its Artist Advancement Grant Committee in 2001 to establish a grant program.

Smart was an Advisory Trustee, then a fellow of the Portland Museum of Art for several terms. She was the founding vice president of the Ogunquit Chamber of Commerce in 1966 and was made an honorary member for life. She served on several Maine State Biennial Exhibitions Committees and was a member of the jury for Maine scholarship awards of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture from 1982-84. Smart was buried in Springfield, Illinois.

Beverly Linney Hallam

November 22, 1923 - February 21, 2013

Beverly was born in Lynn, Mass. on Nov. 22, 1923, the daughter of Alice Linney Murphy and Edwin Francis Hallam. She graduated from Lynn English High School. During her early years, she studied clarinet and saxophone. In 1945, Hallam received a B.S. Ed. from the Massachusetts College of Art and in that year she received a position at Lasell Junior College (Auburndale, MA) where she was Chairman of the Art Department until 1949. Following coursework at Cranbrook Academy in 1948, she received her M.F.A. from Syracuse University in 1953.

From 1949-1962, Hallam was a professor at the Massachusetts College of Art where she taught Painting, Drawing, and Design. There, she taught the first courses in Photography and Theater Arts, and led students to experiment with avant-garde effects in set painting, costume design, lighting, projection, and taped electronic music. She supervised the Saturday Morning High School Art Classes.

Beverly Hallam, Partridgeberry (1978) Acrylic on Whatman paper

An avid photographer, Ms. Hallam traveled to Europe and compiled many illustrated lectures on art subjects which she gave throughout the country. From the early 1950s, Hallam was one of the earliest artist-adopters in the U.S. of Polyvinyl Acetate—or Acrylic—now ubiquitously recognized as a fine art medium. Known for her large airbrushed flower canvases and for experimental printmaking, Hallam had 45 solo exhibitions in museums and galleries and participated in 280 group shows. Her work is in the permanent collections of many museums and corporations and in private collections in the U.S., Canada, France, Belgium, and Switzerland—including those of the Harvard Art Museums, Farnsworth Art Museum, Ogunquit Museum of American Art and National Museum of Women in the Arts.

Although she taught full time, Hallam never gave up painting. Over the course of a practice that spanned 56 years, she experimented with media and approaches, ever open to new ideas and technical approaches to making. In 1963, Hallam resigned from teaching to live and work full time in Maine, first in Ogunquit and then in York.

Hallam had gallery affiliations in Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Florida, and Maine. Her exhibition history included retrospectives at the Addison Gallery of American Art (1971) and at the Farnsworth Art Museum, Rockland (1998). In that same year, Midtown Galleries in New York mounted a large traveling exhibition focused on Hallam’s innovative use of airbrush, and Carl Little’s monograph Beverly Hallam: An Odyssey in Art was published. In 1990, the Evansville Museum of Arts and Science compiled an exhibition in Indiana that toured to five other states. Her work was recognized with several awards, including "Distinguished Alumni Award, Massachusetts College of Art" and "Maine College of Art Award for Achievement as a Visual Artist." The Union of Maine Visual Artists, as part of the Maine Masters Project, featured her brilliant career on film in Beverly Hallam: Artist as Innovator in 2011, directed by Richard Kane.

Hallam maintained an active studio at Surf Point until her death on February 21, 2013. Her papers are held in the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Her legacy includes the conception, with friend and patron Mary-Leigh Smart, of Surf Point Foundation.

View Hallam’s work from a recent retrospective at Cove Street Arts.

May Sarton

May 3, 1912 – July 16, 1995

From “May Sarton, Poet, Novelist and Individualist, Dies at 83” by Mel Gussow, New York Times, July 18, 1995:

May Sarton, poet, novelist and the strongest of individualists, died on Sunday at the York Hospital in York, Me., the town in which she had lived for many years. She was a stoical figure in American culture, writing about love, solitude and the search for self-knowledge. She was 83.

The cause of death was breast cancer, said Susan Sherman, a close friend and editor of her letters.

During a remarkably prolific career that stretched from early sonnets published in 1929 in Poetry magazine to "Coming Into Eighty" her latest collection of poems, in 1994, Ms. Sarton persistently followed her own path and was nurtured by an inner lyricism. She wrote more than 20 books of fiction and many works of nonfiction, including autobiographies and journals, a play and several screenplays. She was best known and most highly regarded as a poet.

Extremely popular on college campuses, she became a heroine to feminists. In 1965, when she revealed that she was a lesbian, she said she lost two jobs as a result. But as with so much in her life, she had no regrets.

In an interview with Enid Nemy in The New York Times in 1983, Ms. Sarton was described as "a commanding, no-nonsense figure with clear blue eyes and a shock of white hair," a woman who lived in "self-imposed loneliness" in a weathered clapboard house on the Maine coast. She had, it was said, a difficult life; her work has been virtually ignored by major critics and she gained her reputation primarily by word of mouth. The poet said, "Women have been my muse."

Recovering from a stroke, and while often in pain from other ailments, she continued to keep a journal, and in 1993 published "Encore: A Journal of the 80th Year." In it, she said, "I write poems, have always written them, to transcend the painfully personal and reach the universal." She added, "It's hard to say goodbye to journals, and if I live to be 85 I might resume one for the joy of it."

In The New York Times Book Review, the novelist Sheila Ballantyne, reviewing "Anger," Ms. Sarton's 1982 novel, wrote: "It is clear that May Sarton's best work, whatever its form, will endure well beyond the influence of particular reviews or current tastes. For in it she is an example: a seeker after truth with a kind of awesome energy for renewal, an ardent explorer of life's important questions. Her great strength is that when she achieves insight, one believes -- because one has witnessed the struggle that preceded the knowledge."

Ms. Sarton was born in Wondelgem in Belgium in 1914, as Eleanore Marie Sarton. Her father was a Belgian historian of science, her mother an English artist and designer. With the outbreak of World War I, the Sartons emigrated to England and, in 1916, to the United States, where her name was Anglicized to Eleanor May Sarton. As she later recalled in "I Knew a Phoenix: Sketches for an Autobiography," her mother carried with her from Belgium a copy of "Leaves of Grass," and passed on a love of poetry to her daughter.

In 1918, the Sartons settled in Cambridge, Mass. At Shady Hill School in Cambridge, the young woman explored her passion for poetry, and then fell into difficulty at high school because she objected to a teacher's statement that Ibsen was immoral. The fact that she did not go to college was, she said, "a great piece of luck; this way, I'm ignorant but I'm fresh." Stage-struck, she joined Eva Le Gallienne's Civic Repertory Theater as an actress. After the company disbanded in the early 1930's, she founded the Apprentice Theater of the New School for Social Research. When her theater failed, she made frequent trips back to Europe, and continued to re-envision her experiences in poetry.

During the 1930's, two volumes of poetry, "Encounter in April" and "Inner Landscape," and a novel, "The Single Hound," established themes that were to occupy her for a lifetime: the many forms of love and the uniqueness of the individual. To support her art, she wrote book reviews and taught creative writing. Her second novel, "The Bridge of Years," published in 1946, was seemingly drawn from life, dealing with the effect of two world wars on a Belgian family. Many of her subsequent novels, including "The Small Room," "Crucial Conversations" and "A Reckoning," centered on women as protagonists. In these novels as well as in her poems, she confronted issues that foreshadowed feminist writing of subsequent decades.

For Ms. Sarton, poetry was her life's work. As she said: "When you're a poet, you're a poet first. When it comes, it's like an angel." Although she never had the full recognition attained by many of her peers, and never won a Pulitzer Prize or a National Book Award, her work generally received favorable reviews and she had a loyal readership. She was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and received 18 honorary degrees.

In "Encore," she admitted to being hypersensitive about criticism. As she once said, referring to a review of her novel, "A Reckoning," a bad review "is a drop of poison and slowly gets into the system, day by day." But nothing could discourage her from writing, not even a series of illnesses. Through her later years, she chronicled her life in journals. In "After the Stroke," a journal published in 1988, she wrote that she had discovered "for the first time perhaps what it takes to grow old," and, approaching 75, was determined to "recover and go on creating."

Speaking about the "rewards of a solitary life," she said, "Loneliness is most acutely felt with other people, for with others, even with a lover sometimes, we suffer from our differences -- differences of taste, temperament, mood." Quietly she waited for the moment to come "when the world falls away, and the self emerges again from the deep unconscious, bringing back all I have recently experienced to be explored and slowly understood, when I can converse again with my own hidden powers, and so grow, and so be renewed, till death do us part." Of Solitude, Mortality, Liberals, Friends and Fires Fruit of Loneliness

Now for a little I have fed on loneliness

As on some strange fruit from a frost-touched vine --

Persimmon in its yellow comeliness,

Or pomegranate-juice color of wine,

The pucker-mouth crab apple, or late plum --

On fruit of loneliness I have been fed.

But now after short absence I am come

Back from felicity to the wine and bread.

For, being mortal, this luxurious heart

Would starve for you, my dear, I must admit,

If it were held another hour apart

From that food which alone can comfort it --

I am come home to you, for at the end

I find I cannot live without you, friend.

From "Words on the Wind" ("Encounter in April," Houghton-Mifflin, 1937)

I watched the psychic surgeon

Stern, skilled, adroit,

Cut deep into the heart

And yet not hurt. . . .

Old failures, old obsessions

Cut Away. . . .

From "Letter to a Psychiatrist"

Here in Maine it is a cold start to the new year as a tempestuous ocean throws up fountains of spray at the end of my field and its ice on the dirt roads where I walk Tamas, my dog. But the cold is not only in the weather -- after all, we expect that, and we are bundled up; the cold is in the heart. I cannot remember a year when I was more aware of suffering and need, more aware of the botch governments make of human lives, more aware of my own helplessness as though the fire in me had frozen at the center.

When Tamas comes in from the snow, he shakes himself, and this evening I tell myself, as the moon rises in a brief respite from storm, that I must find a way to shake myself out of the frozen mood and start the fire going again. Hard times tempt one to run for cover and hide, wait it out, give up trying to act in the face of gigantic problems no one of us is equipped to solve. The temptation is to withdraw.

But, I tell myself, that is not what being a liberal is all about, however put down and cast aside we may be at the moment. Anger lights the fire when I see some people hanging their heads, allowing themselves to be persuaded that government cannot concern itself with the poor, the disabled, the old, the children. We may have failed, but if so we failed because we did too little, not too much.

We have got to warm ourselves back to the certainty that it is only when we lose the connection between ourselves and other people that we begin to freeze up into despair. That connection has to be kept open whatever happens. It is kept open by letters, by unexpected encounters, or by simply contemplating the points of light here or there.

From "Winter Thoughts" (The New York Times, 1982)

"Music I heard with you was more than music." Exactly. And therefore music itself can only be heard alone. Solitude is the salt of personhood. It brings out the authentic flavor of every experience.

Loneliness is most acutely felt with other people, for with others, even with a lover sometimes, we suffer from our differences -- differences of taste, temperament, mood. Human intercourse often demands that we soften the edge of perception, or withdraw at the very instant of personal truth for fear of hurting, or of being inappropriately present, which is to say naked, in a social situation. Alone we can afford to be wholly whatever we are, and to feel whatever we feel absolutely.

From "Rewards of a Solitary Life" (The New York Times, 1990)

Mary-Leigh Smart and Beverly Hallam

Essay by Donna McNeil

In Maine and beyond, Mary-Leigh Smart and Beverly Hallam are mythic creatures. Long time summer folk in Ogunquit and eventually year round residents of York, these two women were patron and painter respectively. Mary-Leigh had been coming to Ogunquit since she was a small child, voyaging by train and then carriage from Springfield Illinois where her father, Leigh Call, was publisher of the Springfield Times. Both Mary-Leigh, her parents before her and Beverly were key players in both the Ogunquit Art Association —organized in 1928—and the Barn Gallery, established in 1959. Both organizations descended from the century-old history of Ogunquit’s Art Colony, which had long- welcomed artists to Maine’s inspirational coast. Charles Woodbury and Hamilton Easter Field with protege Robert Laurent — beginning as early as 1911— offered opposing schools of art in Perkins Cove which brought many artists to Ogunquit, some of whom remained. Preceding the construction of the Barn Gallery, members and friends of the Ogunquit Art Association would gather for jazz and drinks along Perkins Cove. The Cove was home to the Left Bank Gallery, owned by Sidney and Frances Borofsky—parents of Jonathan Borofsky; the artist John Laurent who, as did many artists, lived and worked in a “fish shack”. David Von Schlegell had his sculpture studio nearby and other artists naturally gravitated to the area. Mary-Leigh Smart and her husband Jack Smart, a radio actor, returned from their European honeymoon to reside in the Cove in a house they built called Three Faces East which is now a waterfront restaurant. Beverly purchased a landmark raw edged wood clapboard house on Pine Hill Road, a short drive away.

In 1958, prompted by the need for a larger place to assemble and exhibit, Ogunquit Playhouse-owner John Lane donated land for the Barn Gallery; there still exists a pathway from the gallery to the playhouse. The Barn Gallery was founded by Mary-Leigh and Jack Smart, the artist- community pitched in and donated the labor, the existent structure was built and the Ogunquit Art Association and others began exhibiting their work. Originally a collecting institution, Beverly and Mary-Leigh certainly had a hand in the acquisitions. That collection, the Hamilton Easter Field Collection, is now in the trusted hands of the Portland Museum of Art. The openings at the barn Gallery were jolly affairs: there was a tradition of martinis served punch bowl style in the dry town of Ogunquit, and the vernissage served as a defacto bar. This was the social milieu that surrounded Mary-Leigh and Beverly from early adulthood, on. As was their way, they remained influential supporters forever. It wasn’t until Jack Smart passed away in 1960 that Beverly and Mary-Leigh, returning from an extended European visit, decided to build the oceanfront modernist duplex house on Surf Point Road, and live together. Secreted in the garage was a red Corvette with the license plate CLAM in which Beverly, top down, swanned around town.

Mary-Leigh Smart was always a patron. Nurtured by her mother Mary—a ceramicist and painter—she devoted her life to advancing the creative endeavors of others, readily purchasing works of art that compelled her. These were most often modernist abstractions, although in the foyer, which housed a rotating exhibit of their collection, there was at times a finely rendered realist drawing by Alan Magee of his wife Monica’s blonde braid. Mary-Leigh—who always insisted on the hyphen in her name—had a knack for spotting upcoming artists, buying not for investment but passion. She amassed a Who’s Who of Maine and American art, with a few notable Europeans included. A construction from Maine artist Louise Nevelson and a sound sculpture by Italian designer Harry Bertoia graced her living room, alongside signature mid-century furniture. A defining abstract iron sculpture by John Ventimiglia hails the approach of the house. And of course many works by Beverly Hallam were on view throughout.

Their home at Surf Point boasted not only an indoor salt water lap-pool, but every artist’s dream studio. There Beverly had the time and space to create her signature large scale air brush flower paintings. Her process was meticulous. Extraordinarily organized, she kept voluminous notebooks, recording every idea, every sketch, every color. Conversely, her regimented side was wonderfully offset by her wildly stunning collection of artist- designed and crafted jewelry, and her penchant for lighted ice cubes in her cocktail!

Mary-Leigh and Beverly were at every regional opening, first ones in the door, getting the best look. They seemed to know immediately what they wanted to take home, to live with. They conferred quickly and bought on the spot.

Mary-Leigh, an alumna of Wellesley College where she majored in French and wrote her thesis on Andre Gide, was a lifetime devotee to the institution, attending exhibitions and consulting with Wellesley museum professionals regarding Surf Point Foundation. Likewise, Beverly Hallam—professor at Mass College of Art from 1949-1961— alway held a soft spot for her alma mater. It was there, in the early 1950s, where she was allowed to research and pioneer the use of Polyvinyl Acetate as a painting medium, now called “acrylic.” Both Mary-Leigh and Beverly strongly supported the Gallery at the University of New Hampshire in Durham, where on occasion they purchased pieces from the exhibitions.

Beverly and Mary-Leigh were loyal, pure and simple. And perfectionists! Their standards were intimidatingly high, offset by their extensive generosity and sheer love of life. In the late 1990s they began to slow down their collecting—although at times they simply couldn’t help themselves—turning their attention and resources primarily toward the creation of their legacy foundation. Surf Point Foundation will undoubtedly claim a place in the foremost ranks of coveted residency programs and live on as an enduring tribute to two astonishing and impactful women.